No response made to requests for permission – allowed to be published in scholarly editions on the basis that all efforts made.

Image out of copyright so no permission required.

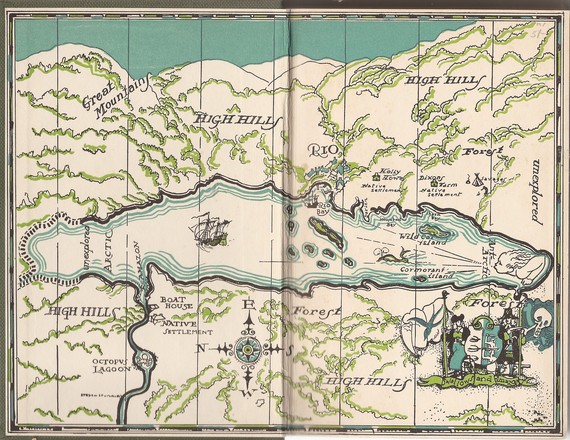

Can you imagine being able to walk along the actual streets of Fagin’s London or retrace Heathcliff’s journey across the moors? What would it be like to explore Treasure Island alongside Jim Hawkins? A successful grant bid to the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK) allows the possibility of experiencing literary space and place in interactive ways that have never existed before.

I am the principal investigator of a research team at Lancaster University working on a project called “Creating a Chronotopic Ground for the Mapping of Literary Texts”. Over the next three years we will try to map literature in terms of both space and time (the chronotope) in a range of ways, including 3D visualisation.

Right at the heart of the project is a core concept that took me a while to work out. For a few years I had been mulling over the problem that literary mapping as it currently exists in academic studies is limited by mapping only onto the real world. It seemed to me far more interesting to map imaginative fictional worlds, but the difficulty was how to do that when there is no “ground” or base map. How can you generate a base map that is authentically linked to the text? What different kinds of map can you have for places that don’t exist in reality?

I stumbled across a model that would work in Russian theorist Mikhail Bakhtin’s account of the chronotope as the central element of literary genre. This enabled me to identify five different kinds of spatio-temporal forms in literature that determine different ways of mapping the fictional world:

• texts that do correspond to a real place in the world (e.g. London in Oliver Twist)

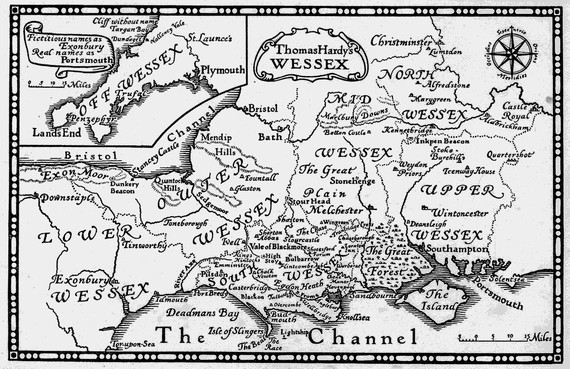

• texts that integrate real and imaginary places (e.g. Hardy’s Wessex)

• texts that have no direct point of reference in reality but create a fictional alternate universe (Middle Earth; Gormenghast; Earthsea)

• bridged texts that start in a real place but move into the imaginary (E.g. Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights Trilogy)

• places that once existed but no longer do so (e.g. the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit)

Advances in digital technology and the spatial humanities then provided a technical way forward. Using existing digital tools from corpus linguistics and combining these with GIS (Geographic Information Systems) my research team will generate unique maps and landscapes out of individual literary works. So the actual language of the text (place names and toponymic descriptions) is used to generate a unique digital version of the fictional environment in the literary work.

One thing that I find really exciting about our project is that we are aiming to create not just static maps but dynamic ones using a 3D environment. Of course, in many ways, gaming environments are strongly “literary” in terms of the use of character, narrative and viewpoint. So it’s surprising that no-one has thought to use the gaming platform in relation to the fictional worlds of literary texts. This has happened for cult works such as The Lord of the Rings but, until now, it hasn’t been taken a stage further and used for classic works of literature. The potential for opening such works up through digital space is enormous.

I should confess that I am not a digital expert by any means, in fact I’m kind of a technophobe – I don’t have a TV and I hate the telephone. So I’m not someone who embraces the lure of the visual in our culture, rather I fear for what it might mean for literary works and the reader.

But at the same time I think humans are above all adaptable, that’s our defining strength, and academics in the Humanities need to take responsibility in terms of shaping and creating digital tools for the next generation. So part of my aim is to integrate the visualisation of fiction with a return to the text itself – to use those aspects of the digital that attract us so powerfully as a way to understand and interpret literary meaning more fully. I’m not visualising literary place for the sake of it or in place of the text (in the way that watching the film becomes shorter and easier than reading the book). I’m aiming to strengthen both by connecting them and moving between mapping and reading.

It may well be that the educational aspects of the project end up having the most impact and for this reason we’ve deliberately included texts that are taught in both primary and secondary schools (Treasure Island; Swallows and Amazons; The Lord of the Flies; Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde). In a pilot project using Minecraft for educational purposes (working with James Butler) we’ve been surprised at the level of interest children have shown and their high-level engagement with first the virtual environment and then with the text that we are exploring in and through it. And I have one other motivating factor. I have a nine year old son who always complains that my research is really boring – maybe this project will make him change his mind!

Professor Sally Bushell,

Head of Department of English Literature and Creative Writing,

Lancaster University, UK

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post UK, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.