Link: http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/david-finch1/universal-credit_b_18430426.html

The pace of the roll-out of Universal Credit has quickened in recent months – and so too have the complaints and reputational hit that the reform is taking.

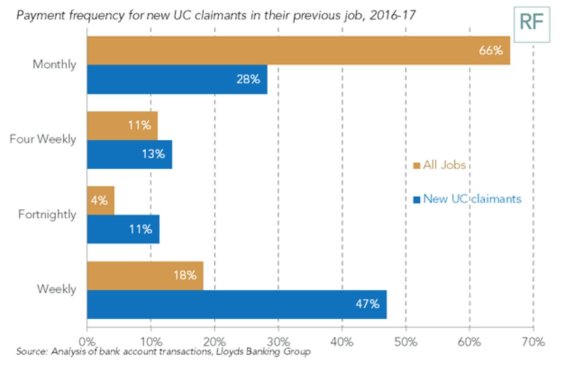

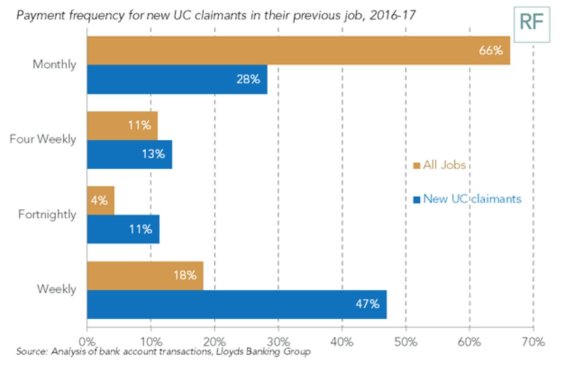

Much of the focus has been on the six week wait before new claimants moving out of work receive their first payment, which is the result of requiring people to wait seven days before earning any benefit entitlement and the view that all families should be got used to monthly payments in arrears. This is a classic case of the design of UC running up against the reality of people’s lives. After all, while it’s likely that 100% of those designing UC are paid monthly, just 28% of new claimants moving out of work and onto UC were paid this way, with the majority (58%) paid either weekly or fortnightly.

The seven day wait should be scrapped and the option of more regular payments introduced. But while bringing more flexibility into the UC payment system can and should be solved they are really just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the design challenges that need addressing.

Far bigger issues will emerge as more ‘complicated’ cases – for example working families with children – move onto the system. The government needs to get onto the front foot in dealing with the frictions that will arise between UC and the self-employed, along with childcare costs and free school meals. Otherwise, the slow drip of bad news risks draining support for UC – and with it a missed opportunity for UC to make a big positive change to our welfare system.

Stepping back from these design issues, the government should also consider the wider question of whether Universal Credit in its current form is fit for purpose in the 21st century – and what can be done to ensure that it is.

Designed in the aftermath of the financial crisis, UC focuses on reducing worklessness – which is now at an all-time low. Workless households may have been a big problem in late 20th Century Britain, but in-work poverty is the big challenge in the 21st Century – and that’s the prism through which to judge Universal Credit. Any government review should consider whether UC helps or hinders the fight against low pay and supports better progression at work.

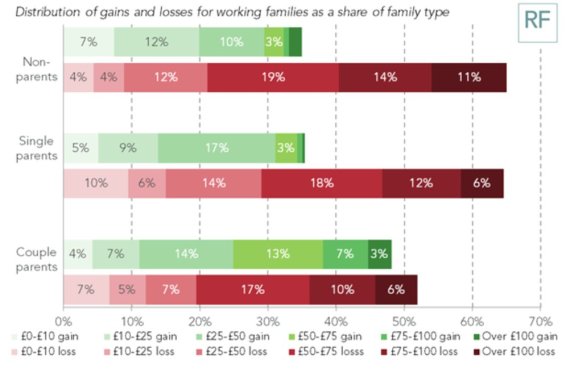

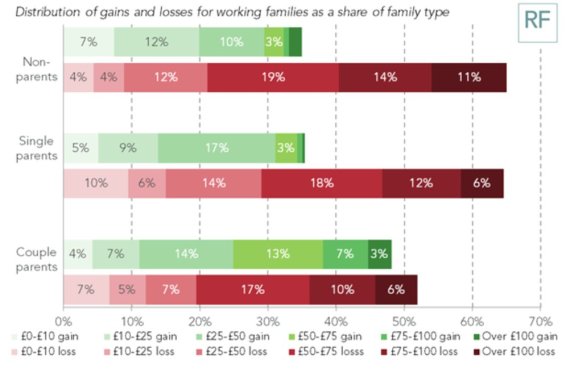

The recent cuts to UC – rendering it less generous than the tax credit system it replaces for working families – put it in a bad starting position for addressing these challenges. On average, working families on UC will be £625 a year worse off. Losses are greatest among single parents: twice as many lose as gain, and those losses are twice the gains.

That’s clearly a problem for living standards but UC is not just about how much support people get, its whether it provides strong incentives to work or not. Less investment in the scheme means it is at risk of undoing the gains in employment made by the tax credit system. Incentives are weaker for many single parents and second earners are at risk of not working at all. Boosting work allowances should therefore be a key first step in making Universal Credit fit for purpose, a point also made Stephen Brien, one of the architects of UC, at our launch event today.

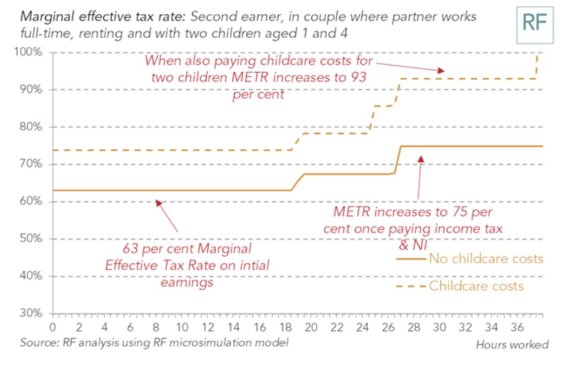

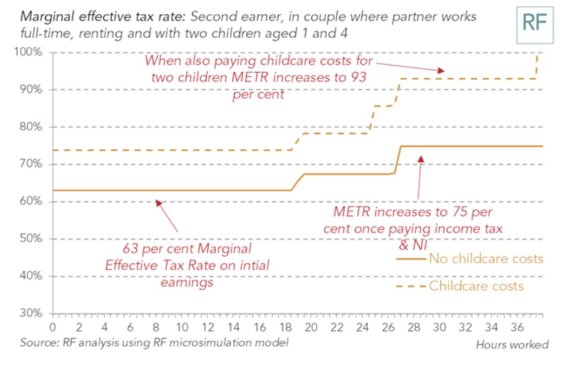

But all of the above will largely just get the system back on track. The bigger goal is to improve on what we already have so that UC helps people get on in work. The good news is that under UC the very highest rates at which benefits are withdrawn as earnings rise have been capped – some on tax credits and Housing Benefit today keep less than 10p of each additional pound earned. However, the marginal effective tax rates in UC remain too high – taxpayers keep 25p of an additional pound. Factor in childcare costs, and some families will keep just 7p of every extra pound they earn.

Some have called for big reductions in the taper rate in UC. Indeed the government reduced the gross rate from 65 to 63% in the Autumn Statement. Big cuts in the taper – for example down to the 55% rate originally envisaged – are desirable but very expensive, especially given wider welfare pressures like the working age benefit freeze. That’s why government must commit to extensive trialling to find the best forms of financial incentives, combined with practical support to help people progress.

The scale of the challenge facing Universal Credit may tempt some to believe that that reform is beyond repair. But that’s not our view – the benefits of Universal Credit are worth fighting for, as long as the government gets back on the front foot of making the necessary changes to make the benefit fit for the 21st Century.

The coming Autumn Budget provide the perfect moment for government to review and relaunch Universal Credit, and it equip to deal with the big living standards challenges of today and the coming years.